A California man accused of failing to pay taxes on tens of millions of dollars allegedly earned from cybercrime also paid local police officers hundreds of thousands of dollars to help him extort, intimidate and silence rivals and former business partners, a new indictment charges. KrebsOnSecurity has learned that many of the man’s alleged targets were members of UGNazi, a hacker group behind multiple high-profile breaches and cyberattacks back in 2012.

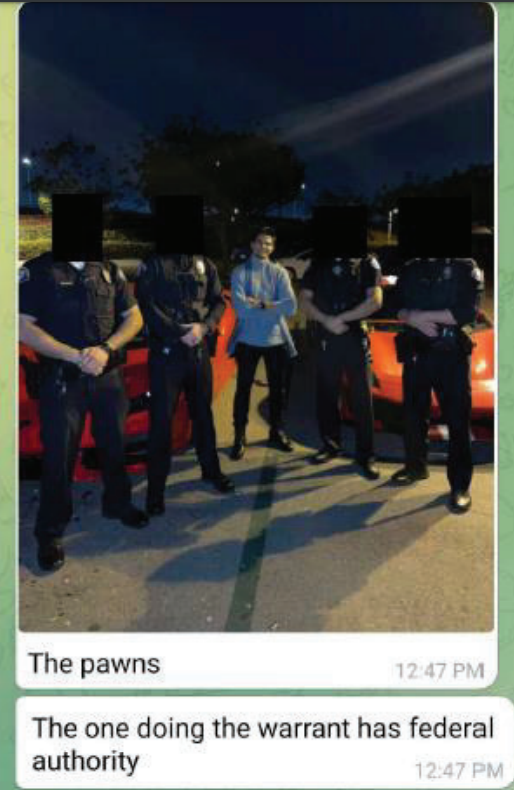

A photo released by the government allegedly showing Iza posing with several LASD officers on his payroll.

An indictment (PDF) unsealed last week said the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has been investigating Los Angeles resident Adam Iza. Also known as “Assad Faiq” and “The Godfather,” Iza is the 30-something founder of a cryptocurrency investment platform called Zort that advertised the ability to make smart trades based on artificial intelligence technology.

But the feds say investors in Zort soon lost their shorts, after Iza and his girlfriend began spending those investments on Lamborghinis, expensive jewelry, vacations, a $28 million home in Bel Air, even cosmetic surgery to extend the length of his legs.

The indictment states the FBI started looking at Iza after receiving multiple reports that he had on his payroll several active deputies with the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department (LASD). Iza’s attorney did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

The complaint cites a letter from an attorney for a victim referenced only as “E.Z.,” who was seeking help related to an extortion and robbery allegedly committed by Iza. The government says that in March 2022, three men showed up at E.Z.’s home, and tried to steal his laptop in an effort to gain access to E.Z. cryptocurrency holdings online. A police report referenced in the complaint says three intruders were scared off when E.Z. fired several handgun rounds in the direction of his assailants.

The FBI later obtained a copy of a search warrant executed by LASD deputies in January 2022 for GPS location information on a phone belonging to E.Z., which shows an LASD deputy unlawfully added E.Z.’s mobile number to a list of those associated with an unrelated firearms investigation.

“Damn my guy actually filed the warrant,” Iza allegedly texted someone after the location warrant was entered. “That’s some serious shit to do for someone….risking a 24 years career. I pay him 280k a month for complete resources. They’re active-duty.”

The FBI alleges LASD officers had on several previous occasions tried to kidnap and extort E.Z. at Iza’s behest. The complaint references a November 2021 incident wherein Iza and E.Z. were in a car together when Iza asked to stop and get snacks at a convenience store. While they were still standing next to the car, a van with several armed LASD deputies showed up and tried to force E.Z. to hand over his phone. E.Z. escaped unharmed, and alerted 911.

E.Z. appears to be short for Enzo Zelocchi, a self-described “actor” who was featured in an ABC News story about a home invasion in Los Angeles around that same time, in which Zelocchi is quoted as saying at least two men tried to rob him at gunpoint (we’ll revisit Zelocchi’s acting credits in a moment).

One of many self portraits published on the Instagram account of Enzo Zelocchi.

The indictment makes frequent references to a co-conspirator of Iza (“CC-1”) — his girlfriend at the time — who allegedly helped Iza run his businesses and spend the millions plunked down by Zort investors. We know what E.Z. stands for because Iza’s girlfriend then was a woman named Iris Au, and in November 2022 she sued Zelocchi for allegedly stealing Iza’s laptop.

Iza’s indictment says he also harassed a man identified only as T.W., and refers to T.W. as one of two Americans currently incarcerated in the Philippines for murder. In December 2018, a then 21-year-0ld Troy Woody Jr. was arrested in Manilla after he was spotted dumping the body of his dead girlfriend Tomi Masters into a local river.

Woody is accused of murdering Masters with the help of his best friend and roommate at the time: Mir Islam, a.k.a. “JoshTheGod,” referred to in the Iza complaint as “M.I.” Islam and Woody were both core members of UGNazi, a hacker collective that sprang up in 2012 and claimed credit for hacking and attacking a number of high-profile websites.

In June 2016, Islam was sentenced to a year in prison for an impressive array of crimes, including stalking people online and posting their personal data on the Internet. Islam also pleaded guilty to reporting dozens of phony bomb threats and fake hostage situations at the homes of celebrities and public officials (Islam participated in a swatting attack against this author in 2013).

Troy Woody Jr. (left) and Mir Islam, are currently in prison in the Philippines for murder.

In December 2022, Troy Woody Jr. sued Iza, Zelocchi and Zort, alleging (PDF) Iza and Zelocchi were involved in a 2018 home invasion at his residence, wherein Woody claimed his assailants stole laptops and phones containing more than $200 million in cryptocurrencies.

Woody’s complaint states that Masters also was present during his 2018 home invasion, as was another core UGNazi member: Eric “CosmoTheGod” Taylor. CosmoTheGod rocketed to Internet infamy in 2013 when he and a number of other hackers set up the Web site exposed[dot]su, which published the address, Social Security numbers and other personal information of public figures, including the former First Lady Michelle Obama, the then-director of the FBI and the U.S. attorney general. The group also swatted many of the people they doxed.

Exposed was built with the help of identity information obtained and/or stolen from ssndob dot ru.

In 2017, Taylor was sentenced to three years probation for participating in multiple swatting attacks, including the one against my home in 2013.

Iza’s indictment says the FBI interviewed Woody in Manilla where he is currently incarcerated, and learned that Iza has been harassing him about passwords that would unlock access to cryptocurrencies. The FBI’s complaint leaves open the question of how Woody and Islam got the phones in the first place, but the implication is that Iza may have instigated the harassment by having mobile phones smuggled to the prisoners.

The government suggests its case against Iza was made possible in part thanks to Iza’s propensity for ripping off people who worked for him. The indictment cites information provided by a private investigator identified only as “K.C.,” who said Iza hired him to surveil Zelocchi but ultimately refused to pay him for much of the work.

K.C. stands for Kenneth Childs, who in 2022 sued Iris Au and Zort (PDF) for theft by deception and commercial disparagement, after it became clear his private eye services were being used as part of a scheme by the Zort founders to intimidate and extort others. Childs’ complaint says Iza ultimately clawed back tens of thousands of dollars in payments he’d previously made as part of their contract.

The government also included evidence provided by an associate of Iza’s — named only as “R.C.” — who was hired to throw a party at Iza’s home. According to the feds, Iza paid the associate $50,000 to craft the event to his liking, but on the day of the party Iza allegedly told R.C. he was unhappy with the event and demanded half of his money back.

When R.C. balked, Iza allegedly surrounded the man with armed LASD officers, who then extracted the payment by seizing his phone. The indictment claims Iza kept R.C.’s phone and spent the remainder of his bank balance.

A photo Iza allegedly sent to Tassilo Heinrich immediately after Heinrich’s arrest on unsubstantiated drug charges.

The FBI said that after the incident at the party, Iza had his bribed sheriff deputies to pull R.C. over and arrest him on phony drug charges. The complaint includes a photo of R.C. being handcuffed by the police, which the feds say Iza sent to R.C. in order to intimidate him even further. The drug charges were later dismissed for lack of evidence.

The government alleges Iza and Au paid the LASD officers using Zelle transfers from accounts tied to two different entities incorporated by one or both of them: Dream Agency and Rise Agency. The complaint further alleges that these two entities were the beneficiaries of a business that sold hacked and phished Facebook advertising accounts, and bribed Facebook employees to unblock ads that violated its terms of service.

The complaint says Iza ran this business with another individual identified only as “T.H.,” and that at some point T.H. had some personal problems and checked himself into rehab. T.H. told the FBI that Iza responded by stealing his laptop and turning his associate in to the government.

KrebsOnSecurity has learned that T.H. in this case is Tassilo Heinrich, a man indicted in 2022 for hacking into the e-commerce platform Shopify, and leaking the user database for Ledger, a company that makes hardware wallets for storing cryptocurrencies.

Heinrich pleaded guilty in 2022 and was sentenced to time served, three years of supervised release, and ordered to pay restitution to Shopify. Upon his release from custody, Heinrich told the FBI that Iza was still using his account at the public screenshot service Gyazo to document communications regarding his alleged bribing of LASD officers.

Prosecutors say Iza and Au portrayed themselves as glamorous and wealthy individuals who were successful social media influencers, but that most of that was a carefully crafted facade designed to attract investment from cryptocurrency enthusiasts. Meanwhile, the U.K. tabloids reported this summer that Au was dating Davide Sanclimenti, the 2022 co-winner on the dating reality show Love Island.

Au was featured on the July 2024 cover of “Womenpreneur Middle East.”

Recall that we promised to revisit Mr. Zelocchi’s claimed acting credits. Despite being briefly listed on the Internet Movie Data Base (imdb.com) as the most awarded science fiction actor of all time, it’s not clear whether Mr. Zelocchi has starred in any real movies.

Earlier this year, an Internet sleuth on Youtube showed that even though Zelocchi’s IMDB profile has him earning more awards than most other actors on the platform (here he is holding a Youtube top viewership award), Zelocchi is probably better known as the director of the movie once rated the absolute worst sci-fi flick on IMDB: A 2015 work called “Angel’s Apocalypse.” Most of the video shorts on Zelocchi’s Instagram page appear to be short clips, some of which look more like a commercial for men’s cologne than a clip from a real movie.

A Reddit post from a year ago calling attention to Zelocchi’s sci-fi film Angel’s Apocalypse somehow earning more audience votes than any other movie in the same genre.

In many ways, the crimes described in this indictment and the various related civil lawsuits would prefigure a disturbing new trend within English-speaking cybercrime communities that has bubbled up in the past few years: The emergence of “violence-as-as-service” offerings that allow cybercriminals to anonymously extort and intimidate their rivals.

Found on certain Telegram channels are solicitations for IRL or “In Real Life” jobs, wherein people hire themselves out as willing to commit a variety of physical attacks in their local geographic area, such as slashing tires, firebombing a home, or tossing a brick through someone’s window.

Many of the cybercriminals in this community have stolen tens of millions of dollars worth of cryptocurrency, and can easily afford to bribe police officers. KrebsOnSecurity would expect to see more of this in the future as young, crypto-rich cybercriminals seek to corrupt people in authority to their advantage.